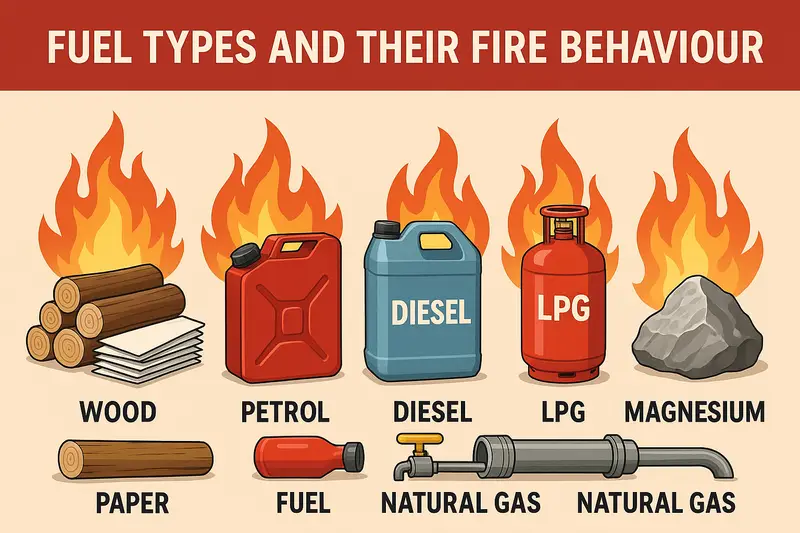

Fuel Types and Their Fire Behaviour, Why Different Fuels Burn Differently and How Fires Escalate

In real fires, fuel type determines how fast a fire starts, how violently it spreads, how much smoke is produced, and whether an incident becomes controllable or catastrophic. Fire investigations consistently show that many fires escalate not because fuel was unknown, but because people misunderstood how that fuel behaves once ignited.

According to HSE fire and explosion guidance, different fuel types such as solids, liquids, and gases behave differently in a fire depending on their physical and chemical properties.

This guide explains fuel types from a practical fire risk perspective, focusing on how different fuels behave during real incidents, where common mistakes occur, and how correct controls prevent escalation.

Why Fuel Behaviour Matters in Fire Safety

Fuel is always present in workplaces, homes, and industrial sites. What changes the severity of a fire is:

- How easily the fuel ignites

- How quickly it releases energy

- Whether it produces flammable vapours

- How it reacts to water or other extinguishing agents

- How much fuel is present in one location

The same ignition source can produce a small controllable fire with one fuel, and a flash fire or explosion with another.

Solid Fuels, Slow to Ignite but Dangerous When Accumulated

Solid fuels include materials such as:

- Wood, paper, cardboard

- Textiles and furnishings

- Rubber and many plastics

- Packaging and insulation materials

How Solid Fuel Fires Develop

Solid fuels do not burn directly. When heated, they release flammable gases that ignite above the surface.

Typical stages include:

- Gradual heating

- Release of flammable vapours

- Flaming combustion

- Hidden smouldering after flames die down

Why Solid Fuel Fires Are Dangerous

- Large amounts of smoke are produced

- Fires can smoulder unseen inside walls, stacks, or furniture

- Structural elements can weaken due to prolonged heating

- Sudden re introduction of air can cause rapid fire growth

Common failure

Large quantities of cardboard, pallets, or waste stored close together with no separation.

Liquid Fuels, Fast Spreading and Difficult to Control

Liquid fuels burn through their vapours, not the liquid itself.

Common examples include:

- Petrol, diesel, kerosene

- Solvents and thinners

- Alcohol based liquids

- Oils and lubricants

Real Fire Behaviour of Liquid Fuels

- Ignition is often rapid

- Fires spread quickly across floors

- Burning liquid can flow into drains and trenches

- Vapours can ignite far from the original spill

Low flash point liquids such as petrol are especially dangerous because they release flammable vapours even at normal temperatures.

Common failure

Using water jets on burning liquids, which spreads the fire instead of controlling it.

Gaseous Fuels, Small Leaks with Big Consequences

Gases mix easily with air and can ignite instantly.

Typical gases include:

- LPG and propane

- Natural gas

- Hydrogen

- Acetylene

How Gas Fires Escalate

- Leaks may go unnoticed

- Gas accumulates in confined or low ventilation areas

- Ignition causes flash fires or explosions

- Pressurized leaks can form intense jet flames

Some gases collect near floors, others near ceilings, which affects where detection and ventilation are needed.

Common failure

Attempting to extinguish a gas flame without first isolating the gas supply.

Metal Fuels, Rare but Extremely Severe

Certain metals become powerful fuels, especially when finely divided.

Examples include:

- Magnesium

- Sodium and potassium

- Aluminium or titanium dust

Behaviour of Metal Fires

- Extremely high temperatures

- Bright, intense flames

- Violent reactions with water or foam

- Molten metal spread

Metal fires are among the most dangerous and are often worsened by incorrect firefighting actions.

Common failure

Using water or CO₂ on metal fires, leading to explosions and splatter.

Fuel Form, Why Size and Shape Matter

Fuel behaviour changes dramatically with form.

- Fine dust ignites much faster than solid blocks

- Thin films of liquid burn more violently than deep pools

- Piles trap heat and promote self heating

This explains why dust explosions, vapour flash fires, and spontaneous combustion occur even when ignition sources seem minor.

How Fuel Quantity Affects Fire Severity

Fuel load refers to how much combustible material is present in one area.

High fuel load leads to:

- Higher temperatures

- Longer burning duration

- Faster fire spread

- Increased risk of flashover

- Structural collapse

Many major fires occur not because materials are highly flammable, but because too much fuel is stored in one place.

Matching Fuel Type with the Right Firefighting Method

Correct extinguishing depends on fuel behaviour, not convenience.

- Solid fuels require cooling

- Liquid fuels require vapour suppression

- Gas fires require isolation first

- Metal fires require special agents only

Using the wrong extinguisher can turn a small fire into a major incident.

Fuel Storage Mistakes That Cause Fires

Across inspections and investigations, the same mistakes appear repeatedly:

- Flammable liquids stored near ignition sources

- Gas cylinders exposed to heat

- Combustible waste allowed to accumulate

- Metal swarf mixed with oil

- Poor ventilation in fuel storage areas

These issues allow fuel hazards to grow silently until ignition occurs.

Practical Fuel Hazard Assessment Questions

When inspecting any site, ask:

- What fuels are present?

- In what form are they stored?

- How much fuel is accumulated?

- Are ignition sources nearby?

- What happens if this fuel ignites?

- Are correct extinguishers available?

- Do people understand how this fuel behaves?

These questions prevent theoretical assessments from becoming meaningless.

Common Misunderstandings About Fuel Behaviour

- “Diesel is safe because it does not ignite easily”

- “Small gas leaks are harmless”

- “Metal fires are rare, so no special planning is needed”

- “Water works on most fires”

These assumptions are responsible for many severe fire incidents.

Who Should Use This Guide

This guide is intended for:

- Safety officers

- Facility and warehouse managers

- Maintenance supervisors

- Fire wardens

- Employers responsible for fire risk control

Conclusion

Fuel type determines how a fire starts, spreads, and escalates. Solid fuels smoulder and generate smoke, liquid fuels spread rapidly, gas fuels explode or flash, and metal fuels burn with extreme intensity. Understanding real fuel behaviour allows better storage decisions, correct extinguisher selection, and realistic fire risk assessments.

Fire safety is not about memorizing classifications. It is about understanding how fuels actually behave when things go wrong.

Fire Triangle Explained: Definition, Elements, Examples and Importance

Heat Sources in Industrial Fires: Causes, Risks, Control Measures and Prevention

Breaking the Fire Triangle: Methods and Applications

Electrical Fire Causes: Detailed Explanation, Scientific Background, Risk Factors, and Prevention